From 0 to 255: Our state’s steady support of a new way to

govern public schools

1.

Introduction – A look back to proposals from 30

years ago. Has the K-12 system changed?

2.

“Self-governing schools” (charter schools) –

from 0 to 255 – numbers, graphs

3.

The “c” word. How the debate about charters

misses the point. The larger questions to ask: Who is in charge of a school? Who

should be? Key words: authority, control, and responsibility.

4.

Charter school law – Language revealing its

central concern with authority, control, and responsibility.

5.

“Who is in charge?” part 1- “Schools as

Units of Change.” A focus on leadership and autonomy.

6.

“Who is in charge?” part 2 - “The State

of Education” from the Colorado Leadership Council.

7. “Self-governing

schools” – A 30-year-old idea? In Colorado, try 1864. Once it was all we knew. Still true for most small rural districts. Consider a list of 10 self-governing

schools that have operated successfully for over 50 years. Not “district-run.”

No need for a central office.

1. Introduction

Another View is looking back at public policy recommendations

from 30 years ago – the Keystone Conference of September 1989 – to see if the proposed

changes, and the hope of a more flexible K-12 system, one that would offer greater

freedom and choice for education and families, have been realized.

Last month’s AV #195 recalled Keystone’s recommendation for

alternative teacher certification, which led to a bill signed by Gov. Roy Romer

the following spring (1990). Another View presented the remarkable

growth of Colorado’s alternative licensure program: nearly one quarter of new teachers

in Colorado (over 750 annually, of late) are now prepared through alternative routes.

Do we have greater flexibility in how we prepare and welcome new teachers to

the profession? Absolutely.

In AV #196 we examine two proposals from three decades ago

that called for a new approach to school governance. They imagined a

fundamental change as to who is in charge—who is responsible—for a

school’s performance. The goal was to place (or return) real authority into the

hands of the school. (Two other policy recommendations, for magnet schools and school

within schools, reflected similar ideas.[i])

FROM the 19 public policy recommendations

supported by a majority of the 225 state leaders at the Keystone Conference,

“Public Education: A Shift in the Breeze,” sponsored by the Gates Family

Foundation. (More information on the conference, here.[ii]) (Bold/capitals

mine.)

Self-governing schools. … Colorado needs

to move at once to empower those principals and teachers who have accepted the

RESPONSIBILITY for the education of their students, with the AUTHORITY they

need to achieve the goals set by the district, state, and federal government.

Such schools should have, as in the case of New Zealand, broad POWERS

in determining how they spend money, structure the curriculum, and conduct the

day-to-day operations of the school. It is expected that many self-governing

schools will have active parental advisory bodies for governing boards. (84% of responses essential or important)

Alternative School Governance Structures. To achieve improved education outcomes for

students, a governing body other than the local school district may be

appropriate. The possibilities range

from the experiment in Chelsea, Massachusetts, where the governance of the

district was turned over to Boston University, to Chicago, where neighborhood

groups have assumed RESPONSIBILITY for their schools, to New Jersey, where

a district was recently declared by the

courts to be educationally bankrupt and was assigned to the state for

management. (58% of responses essential or important)

Unlike the proposal for alternative licensure, legislators brought forth no major policy ideas around school governance the following

spring, or in 1991. This changed in 1992, for by then Minnesota and California

had passed legislation enabling the creation of self-governing schools. (Yes—charter

schools.) The Gates Family Foundation hosted a one-day conference in December

of 1992, bringing leaders from the successful efforts in Minnesota and

California to explain their new laws. Within six months a bipartisan charter

school law was passed and signed by Gov. Romer.

Am I steering clear of the “c” word – for charters – for a

reason? Yes, see section 3. The term keeps us from seeing what was, and what

remains, a central purpose behind the larger change they represent.

Did passage of the Charter School Act bring about dramatic

systemic change? A few graphs (section 2) reveal that, to say the least, the

change in K-12 public education has been huge. The first two charter schools

opened that very fall of 1993. Today we have 255 new choices for families and

students; 255 options unavailable back in the early 1990’s; 255 public schools operating

with a new freedom from state mandates, more firmly in control of their own

performance, much as was imagined at Keystone three decades ago.

But is it a systemic change? A debatable point. After all, most

large school districts in Colorado have not adopted the fundamental principles

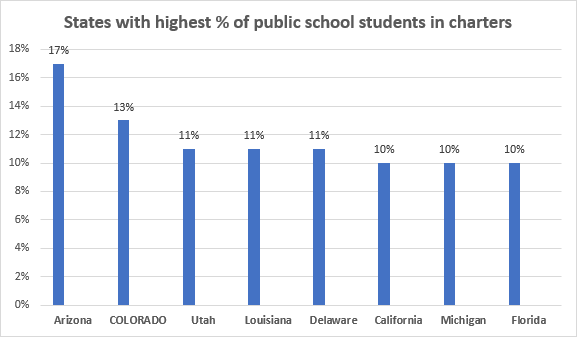

underlying self-governing schools. Nevertheless, as this model now serves 13.7%

of students in Colorado public schools, it is clearly a significant part of the

“the family of public schools,” as the Colorado League of Charter Schools likes

to put it. And in the case of the many strong charters, we now have plenty of

examples to show that self-governance and school autonomy can be crucial

factors in a school’s success.

|

Colorado

Department of Education

|

2016-17 to 2018-19 – from Colorado League of

Charter Schools (CLCS)

1995-96 to 2017-18 from CDE - https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdechart/chartenroll.asp (2012-13 based on my own

addition)

*2019 – email to me from

Colorado League of Charter Schools (CLCS)

Colorado - Percentage of

public school students in a charter school

09-10

|

10-11

|

11-12

|

12-13

|

13-14

|

14-15

|

15-16

|

16-17

|

17-18

|

18-19

|

8%

|

8.6%

|

9.8%

|

10.4%

|

10.9%

|

11.4%

|

12.1%

|

12.7%

|

13.2%

|

13.7%

|

2009-10 to 2012-13 – my

math - from CDE’s reports on total enrollment and on charter school enrollment

2018-19 – email to me from Colorado League of Charter

Schools (CLCS)

“Colorado has

second highest percentage of charter public school students in the country

relative to the total state enrollment.” *

3. The “c” word. How our debate about

charters misses the point.

The larger question

to ask: Who is in charge of a school? Who should be?

Key words: authority and control;

autonomy and responsibility.

Why have I stressed self-governing

schools rather than the easy shorthand, charter schools? Because the

older phrase is less politicized; there is no stigma attached. And because it reminds

us of the essential principle that animated and informed the charter

movement—at least in its early years. In contrast, the “c” word has become a

red flag for so many—a derogatory term associated with not-neighborhood

schools, semi-private schools, and schools-that-refuse-to-serve-everyone.

And more recently, to further obfuscate matters, a term now identified with

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos.

I meet people who are

reflective and cautious when we discuss a range of education issues, but once

the “c” word arises, their mind is made up. They are absolutely certain

(no proof required!) these schools are anti-equity, anti-democratic,

anti-the-public-good, etc. etc. - and what can you say to that?

My generation grew up with

another “c” word that struck fear in the heart: cancer. It is a great blessing

that today – 50 years later—the word does not seem so grim, so fatal. Hope of recovery, of a full-life, is often possible.

In education circles, and among the

public as well, will it take that long for the intense—even

irrational—responses to today’s “c” word, and the charter idea, to

subside?

4. Colorado Charter School law – decision-making,

responsibility, authority

To start, we would do well to return to Colorado’s charter

school law. There we can rediscover the language that reflected largely

bipartisan hopes for what this new kind of school would offer. Key words and

concepts in the state law speak to who makes decisions (people in the

school, not the central office), e.g. control of the budget, the curriculum,

the hiring, etc. This new approach to governance, we said then, meant that

“educators and parents and the community” (not the district) could take the

lead in opening a new school—and running it.

(All bold mine)

22-30.5-102. Legislative declaration. (1) The general assembly hereby finds and declares that:

(a) It is the obligation of all Coloradans to

provide all children with schools that reflect high expectations and create

conditions in all schools where these expectations can be met;

(b) Education reform is in the best interests of the

state in order to strengthen the performance of elementary and secondary public

school pupils, that the best education decisions are made by those who

know the students best and who are responsible for implementing the decisions,

and, therefore, that educators and parents have a right and a responsibility

to participate in the education institutions which serve them;

(c) Different pupils learn differently and public

school programs should be designed to fit the needs of individual pupils and

that there are educators, citizens, and parents in Colorado who are

willing and able to offer innovative programs, educational techniques, and environments

but who lack a channel through which they can direct their innovative efforts.

(2) (e) To create new employment options and

professional opportunities for teachers and principals, including the

opportunity to be responsible for the achievement results of students at the

school site…

On governance, the law made

it clear who had responsibility for the school’s performance.

22-30.5-104 – requirements –

authority - “A charter school shall be

administered and governed by a governing body in a manner agreed to by the

charter school applicant and the chartering local board of education.”

The law – 22-30.5-110

(Charter schools – term – renewal of charter – grounds for nonrenewal or

revocation) also made it clear these new schools would be accountable

for their performance.

Wouldn’t we benefit from returning to

these themes—decision-making, responsibility, and authority—at the heart of self-governance,

when we debate the merits of charter schools?

|

Education Commission of the States

|

5. Where we were asking the question, “Who is in

charge?” – part 1

"Schools as Units of Change Examines Education Transformation in Denver" [v] (April 2018)

“Over the past

decade, Denver Public Schools (DPS) has emerged as one of the most innovative

and rapidly improving big-city school districts in the nation…. Underpinning

this progress has been the commitment of district leaders to sound,

responsive policies – including the idea of schools as the unit of change.

District leaders have embraced school-based autonomy in many forms:

high-performing charter schools have helped to significantly increase the

number of high-quality seats for students, and district-run innovation

schools have helped to diversify school models and expand the impact of

strong school leaders.”

|

For most, a conference held 30

years ago will seem quaint, even irrelevant, when confronting our

current challenges. Not so for the 150 of us who gathered last year at an event

under the bold heading: “Schools as the Unit of Change: Building on Progress in Denver.” (That

very idea might seem subversive in Adams 14, Aurora, and Pueblo. It is clearly

not embraced by all candidates for the Denver school board.) The common

themes at the four sessions that day: (1) successful transformation of large

districts like Denver demands greater school autonomy; (2) effective leadership

at the school level is possible when a principal and his or her school

community are truly confident they can lead—they can make the key decisions on

the budget, hiring, and curriculum—rather than feeling compelled to follow, to carry out the district’s latest

directives.

Empowering

Denver’s School Leaders for Change[vii]

Strong school leaders are stepping forward in increasing numbers to request more school-level control over their campus budgets, time, and focus. How could Denver’s systems and structures better support school leaders as the catalysts for positive change? What are the prerequisites for successful autonomy? How do we prepare a pipeline of educators to lead autonomous schools and networks? Where are the “break the mold” school models? How do we increase racial, ethnic, and gender diversity among our education leaders?” (Bold mine)

Strong school leaders are stepping forward in increasing numbers to request more school-level control over their campus budgets, time, and focus. How could Denver’s systems and structures better support school leaders as the catalysts for positive change? What are the prerequisites for successful autonomy? How do we prepare a pipeline of educators to lead autonomous schools and networks? Where are the “break the mold” school models? How do we increase racial, ethnic, and gender diversity among our education leaders?” (Bold mine)

See also Alan Gottlieb’s summary of this session, “Realizing Autonomy, Embracing Diversity Remain Challenges.”[viii] It began this way:

Even in an environment like Denver that

empowers principals, strong leaders are continually pushing their systems to

gain more autonomy over more areas of their operation.

That was the consensus of principals from all types

of schools — traditional district-run, innovation, and charter — on the

“Empowering School Leaders” panel at the “Schools as the Unit of Change”

convening.

Participants also agreed that more freedom

should lead not only to better outcomes for kids, but also to greater community

engagement. That means doing everything possible to sure that the staff

reflects the community it’s serving. (Bold mine)

Power, leadership, autonomy, freedom…. Aren’t these the vital concepts that are

worthy of an adult conversation, rather than the childish and petty back and

forth around the “c” word?

“Charter

schools are publicly funded, privately managed

and semi-autonomous

schools of choice.”[ix]

National Conference of State Legislatures

|

6. Where we were not asking the

question, “Who is in charge?” – part 2

“The State of Education” from the Education Leadership Council

missed the chance to address this most

basic question. (December 2018)

District

|

Charter

Population

|

District

Population

|

%

of District

|

GREELEY 6

|

5,416

|

22,503

|

24.07%

|

DOUGLAS COUNTY

|

16,207

|

67,591

|

23.98%

|

DENVER COUNTY

|

20,620

|

91,998

|

22.41%

|

SCHOOL DISTRICT 27J

|

3,951

|

18,712

|

21.11%

|

HARRISON 2

|

2,345

|

11,708

|

20.03%

|

Last year also saw

the release of the report from the Education Leadership Council, “The

State of Education.” In over 50 pages, the Council, a distinguished group first

convened by Gov. John Hickenlooper in 2017, presented its “framework and

strategic plan” for education in our state. To no one’s surprise, it reflects

current trends (an emphasis on “student-directed learning experiences,”

students’ “mental, social and emotional health,” and “career and workforce readiness.”)

But how disappointing that it failed to take an in-depth look at school

governance—when, as the “Schools as Units of Change” summit indicated, this

topic is so central to whether or not our large and low-performing school

districts can make progress. And when the most important book on self-governance in America’s urban school districts, David Osborne’s Reinventing

America’s Schools (2017), featured Denver Public Schools, along with the

school districts in New Orleans and Washington, D.C. What concept

does Osborne stress again and again in explaining the shift in control

necessary for urban districts to improve? School autonomy. (See Index-30

references.)

The report fell

short, not only for overlooking the dramatic changes in our capital city (cover

story, Education Next, spring 2019[x]),

but for not reflecting—as I have shown—how our K-12 system is so different than

it was 30 years ago. How different we are, in fact, from most of the 50 states.

Colorado has demonstrated the second greatest support for this “new” way to

enable schools to govern themselves (see page 4). Last year a number of

districts enrolled over one-fifth of their students in self-governing public

schools (see box; data from CLCS). The freedom and flexibility now available to

255 schools shows us an entirely new meaning of “local control”—now in the

hands of these schools, not their district.

Still, a few

excerpts from “The State of Education” reveal that, on occasion, it touched on governance.

Some recognition, at least, around the questions of who makes

decisions and who is responsible for what takes place in our 1,900

schools. For those of us who believe such questions ought to be front and

center as we envision a better way forward, we can make our case by building on

the points below.

Executive Summary

The principles for a world-class education

system were developed through tremendous input from roughly 40 key stakeholders

around the state and tested against input gathered from our public survey and

70+ roundtable discussions. The principles fall under four major drivers of

change. We believe each driver of change represents a necessary area for shared

focus and meaningful progress if we want to achieve a world-class education

system.

Under

one of the four “drivers of change,” Responsive Systems, we read: (Bold,

capitalization, mine)

• Devolve decision-making AUTHORITY,

maintaining accountability for rigorous outcomes

When

it develops that section Responsive Systems and Agile Learners (page 15),

we read:

This subcommittee focused its time on

exploring how to create education systems that are responsive to these changing

– and often daunting—realities. In responsive education systems, we believe

that educators can harness personalization to produce agile learners who can

continually adapt, grow, and prosper in a dynamic and interconnected world. To

do that, we need those closest to students to be responsible for making

DECISIONS about learning environments, we need agile funding systems, and

we need an array of high-quality educational options to meet the various needs

of our diverse society and ensure equitable opportunities for all students.

Essentially, our education system itself needs to model the agility that we

expect from learners.

It

then lists four “principles and strategies [that] offer a variety of paths for

Colorado to attain that aspiration,” including:

Principle 2: Educators and school leaders, in

conjunction with students and families, have the autonomy to make

meaningful DECISIONS about learning while being held accountable for

rigorous outcomes. Responsive systems need flexibility to be reactive to

the diverse needs of learners and the changing world around them. Colorado must

have clear, high expectations for all students and learning providers, while giving

learning providers autonomy in how they achieve those expectations and

support for pursuing innovative practices. Those closest to the students

should be making DECISIONS regarding staffing, scheduling, budgeting, and

instructional systems, so that learning environments can be relevant,

personalized, and contextualized.

Strategy A. Promote flexibility in the

education system.

• Be explicit about what flexibilities

already exist and identify remaining rules and administrative practices that

create specific barriers for innovating schools.

• Ensure flexibilities and autonomies

granted through mechanisms like charters and innovation status are protected.

• Create learning environments that provide

opportunities for flexibility, such as after-school programs, summer

school, special purpose innovation zones, or credit-bearing opportunities for experiential

or work-based learning to occur during the school day.

Surely

flexibility is another key word that would enrich our discussions. It is

related to choice and innovation, as well as to “standards without

standardization.” It represents the opposite of the top-down district model,

the one-size-fits-all system that we universally deride. Isn’t flexibility a

concept we all support? Let’s look at the evidence—unavailable 25 years ago—as

to how the flexibility in the charter law and the way it has been implemented,

especially the waivers from state and districts guidelines, have proved

beneficial for schools and their students.

7.

“Self-governing schools” – A 30-year-old

idea? No, this goes way back. After all, before large school districts

appeared, it is all we knew. Isn’t this how it still works in small rural

districts? And it has always been true for most independent schools, in the U.S.

and in Colorado.

In the 19th century, public schools existed

before districts appeared. Though the term might have seemed silly to our small

schools scattered across the prairie, all were “self-governing.”

Early in the 20th century, much the same. Across

most of America, the idea of a central office controlling what took place in

its small number of schools would have seemed foolish. Decisions were made by

the schools. Even when part of a district, we might have called them “semi-autonomous.”

(Sound familiar?)

In the fall of 2018, the majority of Colorado school

districts (99) served fewer than 800 students. Districts designated as “small

rural” (under 1,000 students) numbered 107. There were 125 districts with fewer

than 2,000 students (for perspective, in 2018-19 there were 25 Colorado high

schools enrolling over 2,000 students). In our small rural districts,

the so-called “central office” often numbers 4 or 5 people—with their offices

in one of the handful of schools. Hard to imagine power struggles when the

school and the district are almost one and the same. Rural superintendents,

principals, and teachers must find it baffling to pick up The Denver Post

and read about those “downtown” mandating what happens across a 200-school

district. Our metro-area buzz about Site-Based Management (SBM) and schools

as the units of change must seem equally strange. For It is all they

have ever known.

If self-governance is a way of life in our smaller

districts, it is absolutely critical to independent private schools here and

across the country. No district offices exist. Leadership is squarely in the

hands of the schools. It doesn’t always work: some fail, many struggle. And

they can be expensive. But one cannot say self-governance is merely a recent

fad, or has not been tested and proven successful. I graduated from one independent

private school in Massachusetts (founded 1797) and taught in another in New

York (founded 1814). Over 200 years. Do we need more proof?

OK, how about in Colorado? Here are 10 well-regarded schools

that have existed for over 50 years, with their founding date. All 10 are members

of the Association of Colorado Independent Schools.

1. St.

Mary’s Academy – 1864

2. Colorado

Academy – 1906

3. Kent

Denver School – 1922

4. Graland

Country Day School – 1924

5. Fountain

Valley School – 1930

6. St.

Anne’s Episcopal School – 1950

7. Colorado

Rocky Mountain School – 1953

8. Steamboat

Mountain School – 1957

9. Vail

Mountain School – 1962

10. The

Colorado Springs School - 1962

In that light, the proposal from the Keystone Conference of 30

years ago is almost recent. Let’s review it:

Colorado

needs to move at once to empower those principals and teachers who have accepted

the RESPONSIBILITY for the education of their students, with the AUTHORITY they

need to achieve the goals set by the district, state, and federal government.

This is how most independent

private schools, like those above, operate. It is how the majority of

Colorado districts operate. And today it is essentially how 255 public

schools in Colorado operate.

Self-governance

is neither a new nor unproven idea. For three decades few states have

done more than Colorado to bring real authority and responsibility back into

the hands of our schools—where it belongs. Do we still believe this is the

right direction for K-12 education in Colorado? Many of us hope so.

End#196

End#196

Previous

newsletters on school governance

AV #23 – Governance (7/2000)

“In an environment where testing and grading schools

crowd out other issues, it is important at look at the very structures we have

created that govern public education. In the 1990’s parents gained more choice

and control over their children’s education. But principals, teachers, and

parents in too many schools still feel our current governance structures leave

them with little control or authority. The system in many districts remains

top-down, and the frustration among those who are asked to lead our schools and

teach our students grows…. We must put in place new forms of governance.”

AV #51 - China and school districts – control or

freedom? (7/2008)

AV #60 - Are we beginning to see a

connection between school autonomy and a better teaching staff? (9/2009)

AV

#99 - Charters and Bureaucracy-A look back, a look ahead: charter law 20

years ago; urban school districts in 10 years (7/2013)

AV #124 - Governance of K-12 Public Education in Colorado - What’s wrong with this picture? (1/2015)

AV #161 -

Schools

with a mission - What if all public schools

(not just charters) were asked to define what they are about? (5/2017)

Endnotes

[i] Magnet

schools. Create

specialized and challenging schools for students within a district or

metropolitan area, or statewide residential magnet schools that would provide

opportunities for gifted and talented students whose potential would otherwise

not be realized. (67% of responses essential or important)

Schools

Within Schools.

Schools need to become more humane institutions that address the needs

of individual children. To accomplish this end, teachers need to see fewer

students for more hours each day and schools must have varied curriculums to

allow children to achieve their maximum potential. Existing schools need to be

restructured (e.g. divide a large school into units of no more than 400

students) so that the existing atmosphere of anonymity is replaced by a sense

of community, and each student is known well by his teachers and peers. (78% of responses essential or important)

[ii] “Public

Education: A Shift in the Breeze” - September 22-25, 1989 – Keystone Conference

“In the fall of 1989, the

Gates Family Foundation convened the conference at the ski resort town of Keystone,

with the stated purpose to bring together a critical mass of Colorado’s leaders

with the nation’s leading experts on educational reform in order that the

State’s leaders can learn first-hand about the successful reforms presently

under way throughout the United States so that they might, if they wish, act to

institute such reforms as seem to be potentially productive, throughout the

state of Colorado. The conference, held September 20-23, was named “Public

Education: A Shift in the Breeze.” Nine national leaders in public education,

representing various efforts at educational reform, spoke to 225 leaders of the

Colorado legislature, educational establishment, and various business and

private sectors.

“Keynote speakers for the

conference were: Dr. Ernest L. Boyer, President of the Carnegie Foundation for

the Advancement of Teaching and Senior Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson School in

Princeton; Fletcher Byrom, retired Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of

Koppers Company, Inc.; Dr. Saul Cooperman, Commissioner of Education for the

State of New Jersey; Dr. John Goodlad, author of 22 books and the Director of

the University of Washington’s Center for Educational Renewal; Dr. Frank

Newman, President of the Education Commission of the States; Dr. Ruth Randall,

Commissioner of Education for the State of Minnesota; Roy Romer, Governor of

Colorado; Albert Shanker, President of the American Federation of Teachers; Dr.

Theodore R. Sizer, Chairman of the Education Department at Brown University and

Chairman of the Coalition of Essential Schools; and Dr. William Youngblood,

Principal of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics.”

FROM “On the Road of Innovation: Colorado’s

Charter School Law Turns 20,” Independence Institute, June 2013

[v] https://gatesfamilyfoundation.org/schools-as-the-unit-of-change-examines-education-transformation-in-denver-2/, a one-day conference hosted by the Gates Family Foundation, held at the Denver Museum of

Nature and Science, April 13, 2018.

[vi] From the Gates Family Foundation’s “brief summary of the current education

landscape in Denver” for the

event. https://gatesfamilyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Schools_as_the_Unit_of_Change_April_13_Reading_and_Agenda.pdf

[x] “Redesigning Denver’s Schools - The Rise and Fall of

Superintendent Tom Boasberg,” by Parker Baxter, Todd L. Ely and Paul Teske, spring 2019 - https://www.educationnext.org/redesigning-denver-schools-rise-fall-superintendent-tom-boasberg/

“Closely connected to

Boasberg’s concern for accountability was his desire to empower school leaders

and educators to inject innovation into the district. He argued that

‘accountability without autonomy is compulsion,’ and that real accountability

for student outcomes requires giving educators control over inputs.”

No comments:

Post a Comment